VINEGAR EELS (How to raise and collect them as easily as microworms)

(Click on Bettas to return to the main betta page or on main site to browse 70 topics ranging from exotic kaleidoscope designs to the strange world of lucid dreaming.)

NEW

COLLECTION TECHNIQUE!!!

In April, Christopher emailed my his technique for collecting vinegar eels. He grows his eels in a jug with the cap threads on the inside of the neck. The jug is filled with growing solution so that the liquid covers the bottom thread. The eels' natural tendency to swim upward drives them up the threads above the level of the liquid. They become concentrated in the threads and can be easily collected using an eyedropper or fine paint brush. I haven't tried this technique myself but it sounds like it should work. Better still, it doesn't require the very high eel concentration my technique needs to work.

Vinegar

eel life cycle information:

Vinegar eels are actually named turbatrix aceti and belong to the

phyla nematoda (nematodes). They are free-living, non-parasitic

unsegmented roundworms and were discovered by Borellus in 1656. They

eat bacteria and fungi that grows in unpasteurized vinegar solutions.

Vinegar eels live an average of 10 months, giving birth to as many as

45 young every 8 to 10 days. A healthy culture can experience a

20-times increase in its population in only 8 days. They thrive over

a wide range of temperature from 60 to 90 degrees. In pure liquid

cultures, such as a mixture of apple cider vinegar and apple juice,

90 percent of the worms will inhabit the top 1/4 inch of the liquid

to be as close to oxygen-rich surface as possible. Their favorite

congregating location is the thin meniscus at the edge of the

liquid/container interface.

NEW!!! Eel

clumping picture!

Six paragraphs down this page is a picture of me using an eyedropper to collect a clump of vinegar eels. The problem is that at the time I took the picture the eel clumps were uncharacteristically small. Below is a picture of what clumping eels more typically look like:

If you are viewing this page at a standard default of 72 ppi, then the clumps will display full size. The length of the clump along the water line is a little over two inches long, representing tens of thousands of eels that can be collected in a second using an eyedropper. The clumps are so dense that very little growing liquid is collected when the eels are drawn into the eyedropper so that you don't have to worry about adding too much acid to the fry tank.

My vinegar eels stopped climbing! My culture had been going along for several months and I decided they might need something more to eat. So, I added six ounces of apple juice. They immediately stopped climbing. I think what happened is that the apple juice reduced the acidity in the liquid, which somehow made them not want to climb. There's still millions of active eels in the jar and I'm working on figuring out how to make them start climbing again. Wish me luck! (Three weeks after this post the eels started clumping again. I started a new culture and seeded it with eels collected from the first. The new culture also took three weeks to start clumping.)

Sheet

mystery solved! Anyone

who's raised vinegar eels has noticed that after a month or so,

large, loose sheets of material can be seen floating around the jar.

No one I've talked to about this knew what it was. Then I noticed it

looked a little like the sheet of brown algae that had plagued two of

my spawns. The next time a set up a vinegar eel culture, I added some

Algae Destroyer by Jungle and after three months there are still no

sheets in the jar. I'm assuming that this is confirmation that the

sheets are algae.

VERY IMPORTANT!!!

I TRIED RAISING A SPAWN ON A DIET OF PURE VINEGAR EELS. THE FRY GREW VERY SLOWLY AND MOST OF THEM DIED BY THE FIFTH WEEK EVEN THOUGH THERE WAS NO SIGN OF DISEASE. I INTERPRET THIS AS INDICATING THAT VINEGAR EELS ARE NUTRITIONALLY DEFICIENT. THEY ARE USEFUL AS A SUPPLEMENT AND FOR CARRYING THE FRY A COUPLE OF DAYS UNTIL THEY CAN HANDLE BABY BRINE SHRIMP BUT I WOULD STRONGLY RECOMMEND AGAINST USING THEM AS THE FRY'S ONLY FOOD.

Three

Vinegar Eel

hints!

Hint #1: Have a thimble handy when you use the eyedropper technique (pictured below) to collect eels. Eels collected with an eyedropper tend to be pulled up as tight clumps. If discharged into the fry tank like this, the clumps fall to the bottom of the tank. Since betta fry prefer surface feeding, many of the eels will be wasted. To gently break up the clusters, simply discharge the contents of the eyedropper into the thimble and suck it back up a few times. This separates the eels.

Hint #2: Even separated, drops of vinegar eels still tend to fall to the bottom of the tank because the els, and the medium they grow in, are heavier than water. This problem can be remedied if there is a horizontal surface just under the fry tank's water line. If there is, in my fry tank it's the top of the power head the circulates the water through the filter system, discharge most of the eels onto this surface. The eels will congregate there and stay near the surface. But... don't forget to scatter a few drops throughout the tank so that all the fry can find them.

Hint #3: If you use the auto-collecting technique explained below, be aware that after several months, when it's necessary to add some more apple juice to the tanks, that if the new liquid level is higher than the old scratched area, you need to sandpaper the inside of the tank at the new level. Also, it may take a week or more for the eels to start clumping again so only do one tank a week. I redid all five of mine at once and only one of them started clumping immediately. Three of the other four took a week to get started and the fifth took two weeks. Had they all stopped producing, I'd have had nothing to feed my fry.

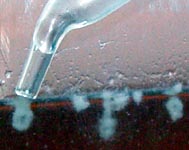

Photo of using an eyedropper to collect eels when the forced-clumping technique is used I discovered that if the inside of the container holding vinegar eels is roughened with sandpaper to creat verticle scratches, the eels will clump up at the roughened area. They can then be sucked up using an eyedropper and fed to fry.

Usually the clumps are larger but even these few contain many hundreds of eels, easily enough for 100 betta fry. The clumps reform quickly. Ten minutes after harvesting these they had been replaced by a new set of even larger clumps.

Aeration experiment To see if providing vinegar eels more air increases the number of worms a culture can support, I added an gently-bubbling air stone to a 1/2 gallon culture. I'll observe it over the next month and try to determine if the number of worms in this culture grows faster that two other similar cultures without aeration.

After several weeks of aeration, it appeared that the density of eels was actually less than those in the unaerated cultures. It would seem that the eels require still water to mate.

A reason why vinegar eels are better than microworms I recently fed some microworms to my fry. The microworms had obligingly climbed up the sides and onto the underside of the lid to their container so I simple removed the lid and dipped it into the fry tank. The worms washed off, the fry gobbled them up, and a lot of mucky stuff ended up on the bottom of the tank. It seems that microworms carry a lot of the mashed potatoes they grow in along with them as they climb. When they're transferred to the fry tank, the potato mixture washes off and settles to the bottom where it can foul the tank. This isn't a problem with vinegar eels so I'd count this as another reason to prefer vinegar eels over microworms. However, this does not consider whether microworms are more or less nutritious that vinegar eels.

How many are needed for a spawn? Eighty percent of my second spawn's food consisted of vinegar eels. By the end of the fourth week I noticed the eels' population density in each of the four cultures from which they had been harvested had dropped to the point where the eels were no longer forming clumps. (Please scroll down to see how to make them do this and make harvesting as easy as collecting microworms.) Each culture consists of one-quarter of a gallon of growing medium teeming with eels. The spawn only had sixty fry. What this indicates is that to have a reliable supply of eels for a normal spawn (150 fry) that'll last for the 40 days fry will eat them, four times more culture would be required. That works out to about four gallons. Note: this requirement assumes that the vinegar eels will be the principle food with baby brine shrimp and microworms given occasionally as treats. If these other foods are used more often, the amount of vinegar eel medium could be reduced.

NEW!!! As well as the eye-dropper collection technique mentioned farther down the page works, I've discovered a slight improvement. The eels are sucked up into the eye dropper in clumps. If they are simply squirted up into the fry tank, they remain as clumps long enough to fall to the bottom of the tank. Once there, they tend to stay close to the bottom in small areas. This means they aren't disbursed and some fish may discover them and eat most of them before the rest of the fry have a chance to get their full share. A simple solution to this problem is to lightly shake the eye dropper a few times to break up the clusters then drip the contents in several widely-spaced locations. This ensures all the fry have an equal chance at the food.

An Interesting Observation

Vinegar eels will occasionally congregate into floating clusters 1/16-inch across. At some point, these clusters start to fall leaving a faint trail of writhing eels in their wake. This looks very much like a animation of comets disintegrating in space. By shining a flashlight sideways through the growing liquid of a jar that has several inches of liquid depth, it's possible to see these faint trails long after the cluster has fallen. What's interesting, and very surprising since the writhing eels look like they'd quickly swim away, is that these trails can persist for up to an hour. I've checked my deep-liquid culture and discovered dozen of perfectly straight columns stretching from the bottom to the top of the jar. Very strange.

A second growing-solution test!

Having determined my eels grow best in solutions that are mostly vinegar, I then began wondering about the effect of varying the size of the apple pieces on growth. I mixed four identical solutions of 3/4 apple cider vinegar and 1/4 apple juice. One I left as is, the second had 1/4 of a peeled apple added in a single piece, the third had the same amount of apple added after being cut into eight pieces, and the fourth had the same amount of apple after it had been shredded. I stirred up my master culture of vinegar eels, collected one cup of solution, and divided this evenly between the four test solutions, being careful to keep it stirred so that each solution got an equal number of eels.

The fastest growth occurred in the solution with no apple. Next came the one with the apple cut into eight chunks, next the solution with shredded apple, and finally, the one with the slowest growth was the one with the apple left in one piece. There doesn't appear to be a pattern to the growth rate relative to how the apple is cut up.

More climbing experiments!

Four days after starting the cultures, the eels in the shredded-apple, no-apple, and chunked-apple cultures began climbing the walls of their containers. At first it appeared that the more finely shredded the apple was, the more the eels tended to climb. But, after this initial episode of climbing there appeared to be no pattern consistent enough to suggest a reliable way to make eels climb. The culture with a single large apple piece has never had eels climb its wall even after two weeks. But, that may be due to the fact that it has very few eels.

I also tried using 240-grit (fine) sandpaper to roughen the inside surface of the container with the idea that a rough texture would make it easier for them to climb. It worked great! Eels congregated and clumped up at the roughened site.

The only pattern I've been able to establish for getting vinegar eels to climb is to achieve very high population densities and keep the containers covered. (Please note, my cultures are grown in large, squat containers with one-inch of growing solution and six-inches of air space. This enables the containers to be closed for long periods of time without starving the eels of oxygen.) I confess that I've run into a brick wall as far as inducing the eels to climb on a reliable basis. To make sure I always have some eels climbing so that they can be easily and cleanly collected, I maintain five growing cultures. It's unusual to not have eels climbing in at least one of these when I need them.

Interesting vinegar eel observations!

1. As a culture's population increases, there is tendency for the eels to collect and crowd together along the upper edge of the growing solution. The worms are constantly wriggling and when their concentrations get high enough, they are forced into such close contact that their wriggling becomes coordinated. They will pack together and wriggle in phase so closely that they begin to look like a single large animal. This in-phase wriggling is very similar to the in-phase, coherent nature of light waves in a laser.

2. Sometimes two groups of in-phase wriggling worms going in opposite directions will meet head-on. When this happens, the pressure at the collision zone can create an area of super-high density where one of three things occurs: The eels bunch up into a tangled knot and this bundle falls to the bottom of the growing solution, Instead of bunching, they form a waterfall of eels, Or the pressure forces a clump of eels upward, out of the growing solution on the sides of the container.

3. After adding vinegar eels to the fry tank, I've noticed that many pairs are joined at the tail. It's not uncommon to see groups of as many as six eels all snagged by their tails and swimming in opposite directions as they try to get away from each other. I assume that eels have a small hook on the ends of their tails that cause them to become connected. This may serve some purpose in mating.

4. The eels aren't able to mantain coherent wriggling in areas where the inside of the tank has been roughened. As a line of wriggling worms contacts a roughened area, they in-phase wriggling breaks down and either the eels form small clumps below the surface or they create a waterfall of eels deeper into the solution.

It may sound crazy, but in some ways studying vinegar eels is almost as interesting as watching fry grow. Unlike microworms or baby brine shrimp, vinegar eels are always doing something interesting.

My vinegar eels are climbing the walls!

Five days after starting four new cultures, three of them, and the master culture from which I pulled seed eels, have vinegar eels climbing the walls. Some are going as high as four inches. In one container they held on for a day, withdrew back into the liquid, then started climbing again. Examining the solution fornulas indicates that the cultures with apples cut into small pieces, the same amount was used in each case, had eels starting to climb before those in jars with the apple left as a single large chunk. But I've also seen eels climbing in a jar that had no apple, just applejuice. It may be that the amount of sugar is too high for the eels and they are climbing to get away from it. I'm considering ways to test this hypothesis. Please check back soon. If I can crack the mystery of how to make them climb, vinegar eels will become as easy as microworms to collect!

Experiment 1. Survey a large number of vinegar eel websites and it becomes apparent that there are as many was to grow these microworms (nematodes, actually) as there are sites with information on them. Some recommend growing mediums that are mostly water, others insist that solutions containing mostly vinegar are better. A few suggest growing them in the dark, others in the light. A few clain the eels don’t need oxygen, others insist they do. The one thing they all agree on is that as valuable as the eels are, harvesting them as food for betta fry is difficult. I decided to conduct some experiments to determine the best growing medium and attempt to develop new harvesting techniques. The results were surprising.

To determine which concentration of vinegar to water induces the fastest, healthiest growth, I inoculated three different growing solutions with the same amount of vinegar eels: three parts water to one part apple cider vinegar, an equal amount of water to vinegar, and one part water to three parts vinegar. Each solution was also given one teaspoon of sugar and a one-cubic-centimeter piece of apple. The cultures were grown in long-necked 12-ounce beer bottles at an average temperature of 70 degrees. After three weeks it was clear that the vinegar eels grew best in the one-part-water-to-three-parts-vinegar solution. The mostly-water solution had very few worms in it and those that were present acted listless. The number of worms had decreased from the starting inoculation. Also, the solution had an unhealthy milkiness to it that I assume was the residue from decayed eels. The equal-parts-water-and-vinegar solution was only slightly better. However, the number of eels in the one-part-water-to-three-parts vinegar had markedly increased and they swam around with great energy. From this experiment it appears that solutions greater than fifty percent vinegar are to be preferred. However, the fact that many people have had success growing them in weaker solutions suggests that in the long run, vinegar eels may be able to adapt to a wide range of conditions. With this in mind, I suggest that anyone beginning a vinegar eel tank should start with the same growing medium in which their starter culture was raised and repeat these experiments to determine for themselves the best solution.

Two sets of the solutions tested above were prepared with one grown in the dark and the other in a normally-lit room. I could not detect any difference between the two after three weeks. This indicates that light is not a significant growth factor.

The three

bottles on the left are the weak, medium, and strong

vinegar

solutions. The three foil-covered bottles on the right

are the same

except that the foil kept them in darkness.

While conducting these tests, I observed that the vinegar eels congregated near the surface of the liquid, particularly toward the edge where surface tension curves the liquid up the side of the container. I assumed this preference indicated a desire to be as close to a source of oxygen as possible. With this in mind, I set up a one-gallon, sealed container with a very shallow depth of culture to maximize the amount of surface area available. Vinegar eels in this container appeared to increase faster than in the tall narrow containers of the first test. This lends support to the theory that the eels require oxygen to flourish. I noted that in this container, the eels had a greater tendency to inhabit the entire volume of liquid rather than fighting for room at the surface. I assume this is because the greater surface area permitted more oxygen to be absorbed into the liquid.

Experiment 2. I tried the three commonest methods of harvesting and found them all unsatisfactory. Filtering through coffee filter paper was slow and many of the smallest worms wriggled through and escaped. Using various sponges to entrap eels was even worse. Washing the acidic growing liquid out of the sponge lost most of the worms and many of those remaining were damaged. The procedure of lightly corking the narrow neck of a bottle with filter floss then filling the top with clear water for the eels to swim into, thereby washing themselves, works but can take overnight to collect enough eels for a feeding. There had to be an easier, faster way... it turns out there is.

Vinegar eels growing in the large-surface-area gallon container presented an even easier solution to harvesting them: vinegar eels climb. Two days after starting the gallon container, I noticed the sides were covered with a fine spider web of thousands of worms. Hundreds could be collected as easily as microworms climbing up the sides of their containers of oatmeal. Regrettably, this behavior is erratic. About half of the time there are enough eels on the side of the container to collect. The other half of the time the sides are clean. I’m currently experimenting to determine how to induce them to climb on a more consistent basis. So far they don’t seem to be attracted to or want to avoid light. Tilting the container to wet the sides usually causes them to climb within ten minutes, but this isn’t always reliable. If the secret to making them climb can be cracked, vinegar eels could supplant microworms as the food-of-choice for betta fry.

One last experiment I conducted was to test how long vinegar eels live in the neutral PH water of a fish tank. In spite of reports claiming that they live for days, this test showed that ninety percent were dead after only 36 hours. I was careful to avoid any physical trauma and made sure that there was no thermal shock involved that might have shorten their life spans.

Besides trying to figure out how to induce vinegar eels to climb on a regular basis, I'm also conducting experiments that compare growth rates with and without pieces of apple, growing solutions with the water replaced with apple juice, and whether having apple pieces on the surface of the growing solution rather than resting on the bottom makes any difference.

One warning about using apple juice: make sure any left over juice is stored in the refrigerator. I failed to do so, with disastrous results. After two weeks on a warm shelf I opened the bottle of cider I'd used on another experiment and the contents exploded over me and the kitchen. The apple juice had fermented and carbonated itself. There was no damage... except to my ego. My wife seemed to get a laugh out of the scene of me standing in shock and dripping with half a gallon of soured apple juice so it wasn't a complete waste.