HUMMINGBIRDS! Pages about hummingbirds care and feeding, zoos with hummingbirds, interviews with hummingbird keepers, and more.

(Click on main site to browse 70 topics ranging from exotic kaleidoscope designs to the strange world of lucid dreaming.)

Bookmarks

to Articles on this Page:

What

to do with an Injured Hummingbird

Hummingbird

Rescue Stories

How

to Make a Better Hummingbird Feeder NEW!!! Winter

feeder warmer!

A

Picture of Four Hummingbirds at a Single Feeder

Feeder

Daily Visitation Profile

Testing

Different Nectar Mixtures

Feeder

Spacing

Hummingbird

Colors

Links

My

Other Hummingbird Information Pages:

Why

hummingbirds, and what's different about these pages

How

to get a wild hummingbird to sit on your finger!

US

zoos with live hummingbird exhibits

Books

about hummingbirds in captivity (with pictures)

Why

hummingbirds as pets, my attempts to obtain them, and growing fruit flies

Links

to other pages about hummingbirds

Results

of online interviews with four hummingbird zoo curators

The

Care of Hummingbirds in Captivity:

3 experts detail hummingbird care in zoos.

Hummingbird

Pictures Techniques

to take good hummingbird pictures NEW

PAGE!!!

What to do with an Injured Hummingbird

I compliment everyone who undertakes to rescue an injured hummingbird. Most people would walk away and forgotten about it. Having said that I have the sad duty to inform everyone that all hummingbirds are protected under many different national and international laws that prohibit keeping them as pets, even if it's in an attempt to save them. They must be turned over to a certified animal rehabilitator. The best way to find someone legally permitted to care for the hummer is to contact local veterinarians. They usually have lists of people trained and certified to care for specific birds. Another possibility would be to call local zoos, get in touch with someone in the bird room and ask them if they have or can recommend a bird rescue person in your area.

In the United States of America all wildlife is under the jurisdiction of US Department of Fish and Game. If you see injured wildlife in the USA, please contact the closest Fish and Game licensed wildlife rehabilitator who specializes in the type of animal you found. (For rehabilitators and their specialties log on the website www.AnimalAdvocates.us. If you still cannot find a licensed rehabilitator trained to care for hummingbirds, please contact your closest Fish & Game office for a referral. Fish and Game southern region (858) 467-4201.) The Animal Advocate site also provides information on rehabititators outside of the USA.

Be aware that as you approach a hummer you appear as to it as a 85-foot tall monster would appear to you. Even if it is only mildly stunned the stress of having such a huge animal hovering over it could send it into shock. So, approach slowly, keep you arms and hands out of site, maintain a low profile, and don't get any closer than you need. First check to make sure that the hummingbird is in no immediate danger. As long as it didn't land on an ant hill, isn't likely to be attacked by a cat, isn't in danger of drowning, stepped on by someone, or driven over by a car, the best thing to do is back off and give it time to recover on it's own. If after fifteen minutes it hasn't flown off, it's a safe bet that more drastic action is required.

Always remember that the panic the bird will feel at being handled may be as dangerous to its health as any physical injures. Always try to prevent stress.

If you feel it's absolutely necessary to pick up the hummingbird, I recommend you first cover it with a small piece of light soft cloth. If it can't see you it may not panic as much. Handling it with the cloth will also prevent you from contaminating the bird or visa versa. Pick up the bird very gently, being careful to avoid squeezing it. Place it in a cage, uncover it, and then either place the cage in a dark room. Do not give the bird any food or water. If it has internal injuries this make make things worse. Also, hummingbirds have very complex nutritional requirements that only trained professionals know how to satisfy. Never put a hummingbird in a tightly closed box. Their high metabolisms require a constant supply of fresh air. Immediately contact a licensed hummingbird rehabilitator for specific instructions.

If you're going to have to hold the bird for several hours while finding out to whom to turn it over to, it will be necessary to start providing food. This may dangerous but with their high metabolisms without some sugar water they can quickly exhaust their energy reserves. Hummingbirds drink a lot of nectar but it's only for the energy they get from the sugar in it. They rely almost completely on flying insects like gnats or fruit flies for protein, fats, and other nutrients. Without access to hundreds of fruit flies a day a hummingbird will quickly die. This is why it's important to act quickly and locate a certified animal rescue person. My recommendation is to set up a small sugar water feeder in the cage to keep him going until he can be turned over to an animal rescue person. The most common solution is one part sugar and four parts water. Never, ever feed a hummingbird a solution made with honey. This will cause a disease called candidice that attacks the bird's tongue. A second feeder of plain water might also be a good idea.

If at any time the hummingbird starts flying, the best thing to do would be to release it in the same area it was found. That way it'll know where all its food sources are.

Another source of information about what to do if you find an injured hummingbird is the The Hummingbird Society. There's a link on the lefthand menu that will take you to a page with information and helpful telephone numbers.

Hummingbird Rescue Stories

The following rescue story comes from Mrs. Jennifer Shade:

On the morning of March 18, 2005, my dog found a baby hummer lying in the parking lot (fortunately, she didn't attempt to eat it). It had already been found by the ants, who were crawling all over it. My husband noticed it was still alive and brought it inside the shop. After we got it warmed up and the ants off of it, I made up a sugar nectar (2 pts sugar/2pts water) and began feeding it by putting a q-tip in the nectar and rubbing it on her (by this time, we decided it was a little girl) beak until she began sticking out her tongue and licking the nectar off of the q-tip on her own.

In for a penny, in for a pound, as the saying goes. After about 2 hours of this... we were able to take a break and I started looking for info on hummingbird care. I found Wayne Schmidt's Hummingbird Information Pages on his site THIS AND THAT and the Hummingbird Society.

I live in Ventura County, CA, and decided that at least she would have a better chance with me than placing her back out in the bushes, as most sources recommend. I figure that she was just fledged out enough to have been startled from the nest. She had feathers on her back, but was just down underneath. We couldn't find a nest anywhere. (Have you ever tried to locate one? They're so tiny,that in the midst of a lot of foliage, they're very well camoflauged.)

Ok, so now we've decided to raise her ourselves. Crazy, I know, but we were committed. I purchased Hummingbird Nectar mix from the local pet store. I had read that sugar nectar alone is not nutritious enough, so I added bird vitimins that I keep for my parakeets, AND I also disolved some "Missing Link" into the nectar because it said it had protein. (Hey, I was shooting for the moon. I had no idea if anything I tried would work. I don't know how to trap bugs, or if I did, how to convince the bird to eat them.)

Our little hummer seemed very content to hang with us. I made her a little aviary,

but she really either wanted to be in one of our hands, or flying around the room. On Saturday, that's just what she did. She flew around the room until she was tired, crashed somewhere and called, and called, and called very loudly until one of us went in to pick her up and put her on the feeder that we had hung in the room. At first, she needed to be directed to eat out of the feeder by actually pushing her beak into the hole. Once it was there, she'd eat her fill and begin to preen while sitting on the feeder. We would leave her at this point. And the whole routine would repeat. I had purchased a red hamster water bottle at the pet store. I put some nectar in it and placed it in her little aviary. Somehow, I was able to make her understand that this was also a source of food. When she was in the box, if she got hungry and started to cry in that shrill manner, I would tap on the top of the bottle until a drip appeared on the end. She would see the drip and drink from it. Eventually, she figured out that she could just shove her toungue around the little ball and get her fill. I was worried at first about this method and thought maybe she wasn't getting enough to eat, so I also supplemented her feeding with an eyedropper. After a few misses, she would get her little beak right in the end of the eyedropper and we could see her tongue going all the way up into the nectar. It was pretty cool.

On Sunday, we had to go visiting some friends in Malibu, so we took her with us because we didn't know if she'd be ok by herself. While there, she asked to be fed a few times, but by afternoon was totally on her own schedule. Monday morning, we figured she'd be ready to release, but she stillhadn't demonstrated that she could find the feeder on her own while flying around the room. Monday night, she finally located the feeder by herself and fed without any interference from us. We knew it was time.

This morning, Tuesday 3/22/05, we took both feeders outside (the regular feeder, and the hamster feeder) and hung them outside. I opened the top of "Anna's" (by now, we've decided she was an Anna's Hummingbird,hence the name) aviary. She looked around a lot, but didn't seem ready to go yet, so I picked her up and placed her on a branch directly below her hamster feeder. She took a few swigs off of the feeder and began looking around. After a few minutes, she flew around a bit and landed back on the feeder. Then she flew over to one of our redwood trees and landed on one branch, then flew again, landed on another branch, did a bit of preening and did some more flying up the tree. Last we saw her before coming to work, she was sitting near the top of the tree having a bath.

We wish her well. A lot of our friends got to see and hold her and feed her. Most of them hadn't been that close to a hummingbird before. Most didn't know that they can open their beaks, or that they have such long toungues. It was a great experience for everyone. It was also 4 days of real work, so I don't recommend it to everyone. It truly touched my heart.

Anna resting comfortably on the lapel of Jennifer Shade's coat.

(Thanks for the great story, Jennifer! One of the particular things I enjoyed about it was how quickly Anna adapted to people and bonded to them, confirmation of what I read in books by people who've been fortunate enough to have them as pets.)

Mr. Troy H. Cheek emailed me the following account of a hummingbird his family rescued:

We live in a rural area in southeast Tennessee and maintain hummingbird feeders on the front porch for the entertainment value. Summer of 2000, after a bad storm, we discovered what we thought was a dead hummingbird in the yard. Much to our surprise, it moved a bit when we picked it up. We sat it back down to see if it would fly away, but after a half hour the best it could do was sit up and wobble a bit before falling over again. We decided to rescue it. Because of the small size, we assumed (probably incorrectly) that this was a youngling who had lost its mother before it was old enough to fly.

We took it inside made it a little house out of an empty plastic peanut butter jar with a folded sock in the bottom. To feed the little darling, we took a yellow flower off a feeder and stuck it on the end of an eyedropper. After a day or two, it perked up and started hopping around in the jar. We added a stick for it to roost on and continued feeding. A few days after that, it started trying to flutter about in the jar, but the jar was too small and it was bending its little wingtip feathers. Trying to ease the bird out of the jar, we discovered it was quite happy to perch on a finger and feed from there.

At first, the bird would barely flap its wings enough to lift off before fluttering back down. About the time we decided the poor thing was never going to learn how to fly, it started doing high speed laps around the ceiling. It either learned very fast or it already knew and just needed to regain its strength It also started ignoring the flower dropper and instead would buzz around the red plastic cup that we mixed the sugar water up in.

We eventually developed a pattern. About dawn little Cupcake (as we called him) would start cheeping and chirping. Whoever got up first in the morning would take the lid off the jar and stick in a finger for Cupcake to perch on so he could be removed. Once out of the jar, he'd buzz around the room for a while until landing on a little perch we hung from the ceiling near the television. When he'd see us raise the red plastic cup, he'd fly over and perch on a raised finger while we carefully tilted the cup so he could drink from it. When he was finished, he'd buzz around the house for a while before coming back to his perch by the TV.

I don't know if he was actually watching TV or just reacting to the noise or movement, or even just hanging out in that room because we spent most of our time there and he associated us with food, but it certainly looked like he was watching TV.

If you raised your hand to yawn or stretch, Cupcake would make a dash for it. If he managed to land on your hand or foot or any other body part, someone had to pass you the cup so you could feed him. Failure to do so would cause him to fly up in your face and scold you.

About sunset Cupcake would appear to fall asleep and we'd transfer him from his perch back to the peanut butter jar.

Cupcake never showed any interest in outdoors as seen through various windows but after the first week or so he did try to follow us out the front door occasionally. After about a month, we couldn't find him and assume he finally made a successful escape without us noticing.

We probably should have released him as soon as he was flying again. My excuse is that my heart is bigger than my brain sometimes.

In a follow-up email Mr. Cheek sent more information about the rescue:

I recently spoke with my mother, who was the primary caregiver for the hummingbird we rescued. She remembers it a little differently than I do.

According to her, the hummingbird was definitely a pre-flight baby when first found as its wing feathers had not yet grown in. She also remembers having it for at least two months, possibly longer. Finally, every night about sunset, my parents would turn off all the lights in the house except for the one in the front room, then prop open the screen door until bugs started swarming the light. The hummingbird would take off from its little perch by the television and zigzag through the room. My mother says that she could actually hear the hummingbird's beak click shut as it snapped up the bugs.

(Since hummingbirds only derive energy from nectar and don't get needed protein of fats from it, it was fortunate that the Cheek family had the forsight to provide a source of insect food to help the hummer survive. They have my highest regard.)

Build a Better Hummingbird Feeder!

Take a critical look at the most common type of hummingbirds feeders and it quickly becomes obvious that there are a lot of thinks wrong with it.

This type of gravity driven hummingbird feeder has several problems. First, while the red-colored sugar water is attractive and may help attract hummingbirds it's also an outstanding solar collector. The liquid quickly heats up and in so doing becomes less palatable to hummingbirds and promotes bacterial grows, algae, and fungus. Additionally, some people claim the red food color may not be good for hummingbirds. Another problem is that the air over the nectar heats up, expands, and as it does so can force enough of the liquid out of the canister to overflow the base, resulting a mess and wastage of hummingbird food. Simply leaving out the dye will help this type of hummingbird feeder keep cooler and cleaner. Even better is to wrap the top in aluminum foil. But, neither of these steps will prevent the worst problem with such feeders.

This type of hummingbird feeder was designed to hold several cups of nectar, enough to last for weeks. While this is convenient to people, it's unhealthy for hummingbirds. Fungus can start growing in the solution in as little as three days. Germs, particularly communicable ones if your feeder is shared by many hummingbirds, can grow even faster, passing disease quickly from one bird to the next. You can dump the hummingbird food every couple of days and wash the container out, but the narrow opening to the storage jar and the impossible-to-get-at nooks and crannies in the base make cleaning such feeders extremely difficult. Besides, this involes throwing out and wasting a lot of hummingird food. Fortunately there's an better solution.

This is a dish-type hummingbird feeder:

The hummingbird food is stored in a shallow dish or bowl under the cover. It doesn't hold very much food, is easy to clean, and won't overflow no matter how hot it gets. But, as good as it is, it can made even better.

What I did was buy 250, 3/4-ounce plastic cups from a restaurant supply store for three dollars. Using indoor/outdoor double faced carpet tape I stuck six of the cups to the inside of the bottom dish right under the location of the yellow flowers used to tell hummingbirds where to feed. These cups work as holders for a second cup placed in them. After mounting it in the garden, I fill each cup with a squirt of hummingbird food and cover the feeder with the top, making sure that the hummingbird feeder holes are over the cups. Then every other day I removed the cups with any remaining solution, discard them, drop in new cups, and fill with a squirt of fresh hummingbird food. This way I eliminate almost all cleaning and am assured that the containers are absolutely sterile. The amount of wasted hummingbird food is almost zero. Instead of having to store gallons in the refrigerator I can now get by with cups.

The hummingbirds seem to appreciate this system and I feel confident that I'm providing them with healthier food.

I mounted the hummingbird feeder on a pole with an ant barrier consisting of the top of a paint spray can with the outer ring filled with vegetable oil.

NEW!!! Winter feeder warmer!

Over the years I've noticed that while most of the hummingbirds in my location fly the 50-miles south to the warmer climate of Los Angeles around November, there are always a few diehards that overwinter in spite of the nightly freezes. I assume they find warm places to spend the night under the eaves of houses where escaping heat warms the air. Even if I take my feeders down I can hear and see these hardy souls flying around during the day. Consequently, I've decided to leave my feeders up to help make their lives a little easier.

One problem with this is that night time temperatures often drop low enough to freeze the sugar water in a feeder. When the birds wake up in the morning and are in their greatest need for nectar they can't feed until the solution thaws. To prevent it from freezing I developed a simple and inexpensive warmer that keeps the nectar warm.

I mounted a deep aluminum pan on the feeder's support platform and secured a block of wood to the center to hold the feeder. Then I placed a 4-watt night light inside it and plugged the light into a automatic timer. The foil pan helps hold in the heat and light from the bulb and concentrate it on the feeder.

The feeder sits in the foil pan. The timer is set to turn on at dusk and the 4-watt light provides enough heat to keep the nectar from freezing. Because the feeder is located under a rainproof cover I don't have to worry about the wires shorting out.

It works better than I had hoped. Not only does it prevent the nectar from freezing, it warms it to a comfortable 65-degrees so that it's a good temperature to help warm up hummers in the freezing mornings. One additional benefit is that the light shining up through the feeder's red top makes an attractive glowing accent on the porch.

Building a Hummingbird Swarm

I've heard of people with large swarms of hummers visiting their backyards because the owners maintain an enormous numbers of feeders. I wondered if I could build up a swarm of my own so in early Spring I added 36 feeders positioned all over my backyard and maintained them for six moths. At the end of that time I counted the number of hummers visiting the feeders to see how many more had discovered my yard as a feeding haven. The result? No change. The population of hummers remains seven. I assume that the reason no more started visiting my feeders is that all the hummers in the area were already working the feeders. There simply weren't any more to pick up. It could be that maintaining the feeders for several years might be necessary to establish a swarm, but considering that not one additional bird discovered them in half a year suggests that any increase would be at best glacial.

2. The feeders I use tend to collect water evaporated from the individual feeding cups and create an environment prone to mold. I tried drilling several holes in the bottom of the feeders to let air circulate, reduce the humidity in the feeder and thereby prevent mold growth. It worked. But... the increased air flow carried off so much water vapor that the individual feeding cups quickly (in as little as two days they dried out to a gummy mess.) Since this was worse than the mold problem I plugged the holes back up. Thinking about the drying problem suggested that if I added a shallow layer of water to the feeder it would increase the humidity so that less water would evaporate from the feeder cups. It worked! The cups stay much fresher than before the holes were drilled. Mold is still a problem but a once-a-week cleaning takes care of it.

3. One day while changing the feeder I almost burned my hand on the red plastic of the top of the feeder. In the intense sun of my high desert location it had heated up to near boiling. Upon checking the feeding solution inside the feeder I discovered that it too was extremely hot to the touch. I doubt that the hummers visiting the feeder would enjoy sitting on a red-hot perch or drinking nectar that was nearly boiling. To remedy this problem I sprayed a miniature umbrella with metallic silver paint and mounted it to shade the feeder. The nectar and perches now remain cool and comfortable. As the picture below shows, the hummingbirds don't seen to mind the overhead shade:

INTERESTING

HUMMINGBIRD PICTURE

While there are hummingbird sanctuaries where over time and with an overabundance of human supplied nectar hummingbirds' natural territoriality breaks down and they learn to accept the presence of other hummers, this is the exception to the norm. In most areas a feeder will be dominated by a single bird with occasionally one other hummer moving in to steal a drink from time to time. Although many of my neighbors maintain feeders, for some reason the local hummingbirds seem to prefer mine, as the following photograph shows:

This picture captured four hummingbirds sitting together to share the feeder. This is extremely rare in an urban environment. Since I use a standard 4-to-1 water-to-sugar ratio the only reason why hummingbirds should prefer my feeder over my neighbors' is that I change the nectar daily, with the result that it always fresh and clean. Scenes like this are most likely to occur in the early morning, when they are hungry from going without food all night, or the in evening, when they need to store up for the night, that their desperation overpowers their sense of territoriality.

NEW!!!

NEW!!! The following short video captures the night time feeding frenzy of the eight hummingbirds currently inhabiting our backyard. Note the high number of Rufous hummingbirds, which were completely absent in the much older images above. They started showing up in 2012 and by 2015 had displaced 60-percent of the Annas.

OPTIMIZED HUMMINGBIRD NECTAR FORMULA:

Every reference I've read states that the best hummingbird food consists of 1 cup of water and 1/4 cup of sugar. I decided to test this by mixing up three batches of it: one at the standard formula, one with 1 tablespoon less sugar, and one with one tablespoon more sugar. I set up identical feeders in the same location and rotated them regularly so that one wasn't used more than the others out of habit.

After several feeding cycles it was obvious from the amount of hummingbird nectar consumed that the standard formula was what the Calypte Anna hummingbirds in my area prefer.

Looks like the books were right!

FEEDER DAILY VISITATION PROFILE:

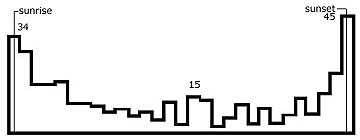

I placed a video camera in front of my feeders and recorded an entire day of hummingbird visitations to determine when they are most active. I counted how many visits the feeders got during each half hour and plotted the results on the following bar graph:

The numbers on the chart indicate the total number of visits during the half-hour bar they are closest to. The most active times are 15 minutes before and after sunrise and sunset. In the early morning the birds are more likely to sit for long periods of time to soak up nectar to replace energy lost during the long night. In the evening they are more prone to fight others away and tend to make shorter stops.

I theorize that they are more willing to share feeders in the early morning because they are close to starving after sleeping all night. Under such conditions they are more interested in getting food than protecting their territory. In the evening they aren't particularly hungry so the drive to protect a food source dominates their actions.

HOW FAR APART DO FEEDERS HAVE TO BE SO HUMMINGBIRDS DON'T FIGHT OVER THEM?

To answer this question I set up two identical feeders and waited for them to be accepted equally by the five hummingbirds frequenting my back yard. I then began moving them apart ten feet every other day to see when the dominant hummingbird quit trying to defend both of them.

Even with the feeders 80 feet apart he never relinquished one in favor of the other. What this told me is that a hummingbird does not defend a feeder as much as a territory. Any feeders within this territory will be protected.

In the urban environment, I suspect a territory is the typical backyard. Trees and walls create an easily identifiable boundary and make it hard to keep more than one yard under protective observation.

If this is correct, then I'd hazard a guess that the answer to this article's question is that the feeders need to be in different areas that are defined by fixed boundaries. In the case of the typical home, this would be the front yard and the back yard. This doesn't mean that multiple feeders can't be set up in one area and not be serviced by many hummingbirds, only that such feeders will only have one dominant bird. Feeders in the front and back yard might support two dominant males.

This might not hold for open rural areas where the dominant hummingbird can easily observe large areas of land.

Hummingbird Colors NEW FEATHER CLOSE-UP PICTURE!!!

While the bulk of a hummingbird's body is covered with normally pigmented feathers like most other birds, the area under a hummingbird's throat usually has a patch of iridescence that's not only brilliant, but can change color when viewed from different angles. Here's how hummingbirds create these stunning colors:

White light is actually composed of a wide spectrum of colors from infrared to ultraviolet. Each color can be thought of as a wave. The distance between two crests of such a wave is called it's wavelength and given the Greek symbol lambda (an upsidedown "Y".) Light wavelengths are very short. For the central yellow-green portion of the color spectrum the human eye sees, the wavelength is only 0.0000219 inches.

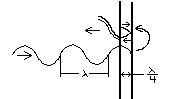

The iridescent color of a hummingbird's throat is the result of a process called "interference," where light waves of one particular wavelength reflecting off two closely spaced surfaces are strengthened whereas light of any other wavelength is weakened. The result is that white light heading toward these surfaces is reflected as a single color. Consider the picture below:

On the bottom, a light wave approaches two transparent surfaces on the right. As it hits the first surface, some of the light is reflected back toward the left (this reflection has been shifted upward slightly so it's easier to see.) This first reflected wave is the lower of the two closely spaced waves moving to the left from the first surface. Due to nature of reflections the hills and valleys of the reflected wave are flipped upsidedown relative to the incoming wave. The part of the wave that passes through the first surface hits the second and is similarly reflected. Because, in this case, the two surfaces are one-quarter of a wavelength apart, the hills and valleys of the wave reflected from the second surface will line up on top of the reflected hills and valleys from the first surface. In so doing the two reflected waves will strengthen each other and appear bright. If a different wavelength is reflected from the same surfaces, the hills and valleys from the second surface will not line up with the first wave and the reflected light will not be as bright. In fact, if the new light wave has a wavelength that's exactly half the length of the wave in the first example (so that the distance between the two surfaces now appears to it to be lambda/2) the valleys of one reflection will line up right on top of the hills of the other and they will cancel completely.

This example shows what happens if light strikes the surfaces straight on. If the light comes in from a different angle the effective distance between the two surfaces is increased and the wavelength of the color of light which will be strongly reflected also has to increase.

It's not necessary to have the surfaces separated by only one-quarter of the wavelength. Any whole number of full wavelengths can be added to the one-quarter needed for the interference and the process will still work. For example, surfaces separated by 1.25 and 2.25 lambda will work the same as those that are only 0.25 lambda apart.

The iridescent portions of hummingbird feathers contain millions of tiny transparent air-filled cells. The fronts and backs of these cells provide the two surfaces needed to create the interference reflections that selectively reflect some colors stronger than others. These cells are stacked many layers deep and each layer helps purify the light to a single color. The following close-up is of a feather from an Annas hummingbird (found in a hummingbird nest - I have no idea how it got there since I assume it's the females that build nests.)

The axis of the camera was perpendicular to the plain of the feather (aimed straight down at it) and the light was positioned to the top of the frame and angled up 20 degrees from the plain of the feather, or equally so, 70 degrees down from the optical axis of the camera. Increasing or decreasing the angle of the light or camera axis by only five degrees is enough to extinguish the iridescence. This feather is only 1/4-inch long so this image represents a 20x enlargement.

These feathers are so small that sixty are required to to cover the head of an Anna's hummingbird.

While most hummingbirds have the iridescent portion only on the throat, there are several, like Damaphila Julie, whose entire bodies are iridescent.

Links:

NEW

LINK!!! http://fohn.net/hummingbird-pictures

The Hummingbird Society

While

cruising around the Internet I found the following site:

(http://portalproductions.com/h/)

which had a nice layout and many interesting pages about hummers.

The "Links" page is particularly excellent.

http://www.humabot.net

is another interesting site with many pictures of hummingbird nests

with eggs.

A visitor to this page sent me a link to a great page with pictures of a hummingbird egg in the wild hatching and growing to maturity. This link was active as of November, 2004. Unfortunately, it died soon there after. The URL is:

http://community-2.webtv/hotmail.com/verle33/HummingBirdNest.html

www.AnimalAdvocates.us Source for animal (and hummingbird) certified rehabilitators

Return to homepage to browse 70 other topics: everything from Knitting Nancies and rocket engines to the strange world of lucid dreaming.